In the summer of 1942 my father, Gerald Churchill, was serving in North Africa as a lieutenant in the 12th Lancers (an armoured car regiment attached to the 1st Armoured Division of the British Army).

On the eve of the 2nd battle of Alamein. on reconnaissance in the desert with his commanding officer, Colonel Peter Burnes, they approached what appeared to be a convoy of their own troops; this turned out to be a group of captured British vehicles being used to transport German troops, and by the time this fact had become clear to them it was too late to make good their escape. They were overwhelmed and taken prisoner.

Shipped off to Italy by their captors, they spent that winter and spring in various prisoner of war camps around Italy. By the following summer both my father and Peter found themselves in PG 49, an orphanage repurposed as a prison, in the northern Italian village of Fontanellato near Parma.

While they were thus occupied the war moved on… The battle of El Alamein, which they had so narrowly missed taking part in, was a turning point in British and American fortunes and led fairly quickly to the comprehensive defeat of German and Italian forces in North Africa.

Between the Americans and the British there were now differences of opinion as to the best strategy to pursue; The Americans were broadly in favour of now concentrating their efforts upon the invasion of Northern France from Britain in 1944; the British, on the other hand, felt that, while they were on the front foot in the Mediterranean theatre, the invasion of Sicily and Italy would be the most productive course of action, Winston Churchill, optimistically, characterising Italy as ‘the soft underbelly of Europe’.

The Americans, reluctantly, went along with the British strategy for the time being and the summer of 1943 saw the Allied invasion and occupation of Sicily and, at the start of September, American and British forces landed in the south of Italy, at Salerno and Taranto, and began to fight their way up that long and mountainous country.

On the 8th of September, timed to coincide with the landings, it was revealed that the new Italian government, who had recently deposed and arrested their pro German dictator, Benito Mussolini, had also secretly signed an Armistice, surrendering unconditionally to the Allies.

Hitler, however, as soon as Mussolini had fallen, had anticipated just such a situation and had started to build up a strong German military presence throughout Italy. The Italians may have had enough, but he had not the slightest intention of surrendering, and so simply set about taking the country over and preparing to defend it against all comers .. including his former allies, the Italians.- should they be so unwise as to resist him….

As the POW camps in Italy were run largely by Italian forces, the camp commanders now received orders from their government to release all their prisoners of war and to try and prevent them falling into German hands.

Accordingly, on the day following the announcement of the Armistice, the Italian commandant of PG49, a Colonel Eugenio Vicedomini, opened the prison, courageously remaining in place himself to face the imminent arrival of the Germans. (He was, as a consequence of this decision, to spend the rest of the war imprisoned in the notorious German concentration camp of Mauthausen, where his health was so badly damaged that he died upon his return to Italy at the end of the war).

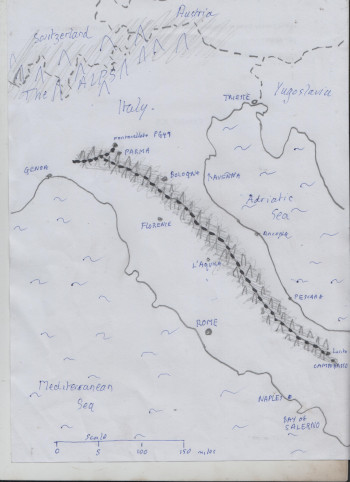

What follows is my father’s account of his two month, 550 to 600 mile trek through German held Italy, following the high ground of the Apennine mountains, at first in the company of his former commanding office Peter Burnes and another 12th Lancer Lieutenant Van Burton, and finally on his own, in order to rejoin the allied forces, wherever they might be.

Alongside his account I have included a few brief excerpts and updates from a couple of other escapers from PG49 who recorded their experiences in this autumn of 1943, as well as following the entries in my mother Elizabeth’s diaries back home in rural Oxfordshire.

Armistice and release …….. 8th September 1943

West – to the river ….. 11th September 1943

Gerald, Peter and Van now set off with the loose overall intention of heading west and then, probably North, with either France (semi neutral) or Switzerland (fully neutral) as eventual goals. Peter also had some friends who lived near the French border and thought that they might be able to take refuge with them. The general feeling among the newly liberated prisoners was that it would not be long before the Germans were forced to abandon Italy altogether and so they would not be needing to hide for long.

However these ideas were vague and not fully formed and they still had no clear view of the larger picture at this point…the information that reached them was usually sketchy, often inaccurate and sometimes plain wrong. The sense of optimism produced by their sudden freedom was soon to fade as the full difficulty of their position became clearer.

The Allies had in fact not made any landings in the northern part of Italy – the commotions that they had heard of in the Genoa and La Spezia directions were bombing raids and not landings, The main, predominantly American, landing at Salerno, near Naples, was still being hotly contested by the Germans and until around the 15th of the month it was not at all clear who would prevail. The British landings at Taranto were initially successful, but, being about as far south as it was possible to be, could not be expected to offer much hope to escaping prisoners more than 500 miles away in the North of the (now german occupied) country for some time yet. Salerno, for that matter was not exactly round the corner , being well the other side of Rome – which itself was some 300 miles distant.

Nor were they yet fully aware of the serious jeopardy that the Italian country people would be placing themselves in by offering escaping prisoners help and shelter. One of the most remarkable aspects of the accounts of all the fugitives is the almost inevitable hospitality that they would all be offered by Italians of every station in life; this particularly so when viewed in the light of the ferocious penalties for harbouring escapers that were promised, and often enacted, by the German occupiers.

Back in rural Oxfordshire my mother, Elizabeth, at home with their young daughter Caroline, was following events as closely as she could. But the flow of correspondence via the Red Cross was not always a streamlined affair… On the 6th of September she records the receipt of a card from Gerald dated 24th of June, (promptly dispatching her own 66th missive by return)… so she, as so many other families and spouses of soldiers and prisoners, was very much in the dark as to how the unfolding events that she was hearing and reading about in the Press were affecting her missing husband. On the 9th of September she recorded in her diary the fact of the Salerno landings; by the 11th she notes “news from Italy most unsettling” and on the 13th, hearing of the sensational liberation of Mussolini by German paratroopers, notes that she “feel(s) frantic about G”

About 600 men had walked out of PG49 on the 9th of September and were now, a day later, having to make difficult choices as to how to use this new found freedom… firstly whether to stay or go, and then, if the latter, where, how and with whom??

Here are a few PG49 prisoners whose experiences have been recorded either by themselves or by others.

Lieutenants Douglas Clarke and John Birkbeck were early adopters of the Swiss option, setting off immediately on foot for neutral Switzerland. In terms of distance this was the shortest route to take, the swiss border being not much more than 100 miles away.

Colonel Hugo de Burgh (the senior British officer of PG49) and Lieutenant Reggie Phillips managed to get a lift to Milan, from which city they too would eventually continue on toward the Swiss border.

Dick Carver, General Montgomery’s stepson, (a connection of which his captors were, fortunately for him, unaware) had been captured under very similar circumstances and at almost exactly the same time and place as Gerald and Peter. He had also ended up in Fontanellato,and now opted to head south, at first as part of a group of 12, quickly reduced to just one travelling companion, with the aim of rejoining his famous stepfather somewhere in the south of the country. .

Stuart Hood, who had paired up with his Gurkha friend Ted, describes his more relaxed approach to solving this problem.

“ We, two men in their late twenties, with nothing in common except the shock of capture and the boredom of captivity,… had agreed to make for the hills together, but not right away… For a couple of days we lay in a green gully, sleeping and planning in the sun. The others disappeared by 2’s and 3’s. We sat and discussed where the Allies must land… if they were delayed more than a few days, then we would start walking|”

Others found themselves not quite so well in control of their own destiny…

Eric Newby, who was later to write a book about his experiences at this time, had needed to be evacuated from PG49 on horseback as he was suffering from a broken ankle but had then, on medical advice, been returned to the local hospital where he now found himself under guard and with the clear prospect of being recaptured as soon as the Germans turned up. However, as his luck would have it, there he met a young woman, who, with help from her family and friends, was to help him too escape the clutches of the Germans,,, at least for the time being.

By the reckoning of Ian English, another inmate of the camp who later collected and published many of the stories of the adventures of the prisoners that autumn, only around 5% of the escapers actually made it as far as the Allied lines … by this metric out of the 6 or 7 hundred prisoners held at PG49 it was but the smallest minority – not more than 30 to 40 men – who would be successful in this endeavour.

Gerald, Peter and Van set off to see whether they could place themselves in that small minority.

‘And back again’ ……. 24th September 1943

Having now been free for a fortnight they had gained a clearer idea of their situation; the Italian population had proved to be largely friendly, they had found that the German occupiers could, with care and good fortune, be avoided and that it was possible to move around fairly freely on foot. They had also come to realise that their present course was unlikely to be profitable and that they now had to retrace the hundred or so miles that they had already walked and start off again in a completely different direction.

They were almost certainly unaware that already some of their fellows had safely crossed the Swiss border, a distance of about 120 miles from PG49 – to be fair they had agreed to disregard the option of this destination as having the major disadvantage that they would then be interned there for the rest of the war,- nor were they aware that those escapers who had decided to make use of the public transport system of trains and buses were doing so with a surprising degree of safety and success.

Their best course of action, they now agreed, looked like being to continue on foot and try and reach the Allied forces, currently fighting their way up from the bottom of the country, some 600 miles away at this time. In order to do so on foot, while keeping to the less populated higher ground that they were beginning to recognise as their safest option, they needed to first head eastward, in order to get further into the mountainous spine of the country that would then allow them to follow their southward trajectory.

In other news….

Eric Newby, meanwhile, had by now made good his escape from the hospital, with the help of his new girlfriends father, and had been spirited away from there, under the nose of the Germans and with not a few alarms, eventually to a hiding place in the mountains where he was to stay for some time. The night that my father and his companions had spent in the relative comforts of the rectory at Cornolo, Eric had spent lying concealed in a hastily dug “grave” with a false roof of planks and turf and a bottle of wine to keep him hydrated until someone could safely come and release him the next day…hopefully!

Hugo de Burgh, with his companion Reggie Phillips, was, on that same night, within sight of the Matterhorn and freedom, of sorts, in Switzerland.. But they still had some difficulties ahead….

While the two lieutenants who had set off so smartly on the 9th of September, Douglas Clarke and John Birkbeck, had been the first to reach their goal, arriving at the Swiss border some ten days ago, on the 14th. .

Stuart Hood and Ted had, as planned started walking after a couple of days, and were currently in the hills above Fidenza working on a hill farm …” from treading the grapes we ran out one day to watch the bombing of Fidenza… smoke and explosions echoing up into the hills. ‘you can see what rich people they must be these Americans,’ remarked their host, ‘they knock things down and don’t care’”

Dick Carver, with his travelling companion “the Dean” narrowly avoided being recaptured on the 20th of September. As Tom Carver, in his account of his fathers journey records , they had been invited in to an inn when “suddenly a woman broke in yelling Tedeschi Tedeschi (germans germans). There was panic as the inn emptied into the street while two German soldiers tried to force their through. Richard and the Dean grabbed their sacks and raced out of the back door of the pub, through a garden and over a low fence. The Dean, slower and older, tried to jump the fence and failed. One of the Germans emerged from the inn and yelled at him to stop. But he managed to get up and half fall and half clamber over the rickety wooden structure and to run down the slope after Richard. For several hours they lay on an island in a dry riverbed listening for sounds of pursuit, but none came. It was their first brush with the Germans – a sign that life was going to become more challenging. After that they resolved to stay on the high ground…”

As for Elizabeth, now visiting friends in Devon, she had just received an old card from Gerald dated February 2nd…This had done little to put her mind at rest, and that night she wrote that she felt ‘very gloomy about Gerald’.

Into the mountains …….. 10th October 1943

They now found themselves not so far from their starting point,with the long mountainous spine of Italy stretching away to the south of them, offering a direct – and hopefully clear – route down toward the southern battlefields.

While they had been walking to the River Trebbia and back again the invasion of Southern Italy had started to gather momentum.

Taranto, Salerno, Corsica, the city of Naples, Termoli, Foggia and its airfields were all major allied gains in the first month of their invasion

However these successes were all more than 400 miles away and the Germans were now preparing to vigorously contest any further progress in a landscape that strongly favoured the defender. They may well have felt themselves on the back foot, as one can perhaps deduce from both their acceleration of their plans to deport Italian Jews to the extermination camps, and their theft of huge quantities of Italian wealth ..some 119 tons of Italian gold were taken from Rome toward the end of September… but they were far from beaten. To make matters worse, and to ensure that the Italian campaign was not going to be concluded any time soon, the Allies, upon American insistence, were already beginning to pull troops out of Italy in order to have them ready for next year’s assault on Normandy.

But as far as the escapers were concerned little could be seen to have changed, and their task, although now perhaps a bit more familiar, remained the same; a long and arduous walk in the mountains.

Stuart Hood commenting upon the difficulties of making progress in these rugged mountains wrote; “If our progress was slow we could plead that the terrain did not help us. The northern slopes of the Apennines are bare and eroded. Ridges like the fingers of a bony hand run up into spines and watersheds. The hills are riven by torrents and breached by 4 rivers; the Taro, the Parma, the Enza and the Secchia. We waded all four”

Dick Carver and the Dean, by virtue of having decided from the start to head south, were about 10 days in front of Gerald, Peter and Van. On the first of October they came to a Franciscan monastery in the beech woods near Cupramontana. …

“Richard rang the bell while the Dean waited round the corner in case of an unfriendly reception. The door was opened by a well fed monk who laughed at their caution and waved at the Dean to come out of the shadows.

“We have another British officer resting here, who is sick” said the monk.

“Can we see him” asked Richard.

They were shown into a monk’s cell where they found an Englishman dressed in pyjamas and lying in clean sheets looking perfectly healthy.

“Good afternoon. I’m the 6th Earl of Ranfurly”

The Dean recorded in his diary;

“We saw Lord Ranfurly in almost forgotten luxury, sitting up in bed with the remains of a very good lunch of mutton and wine on a tray by his side, and although one could hardly complain of the cold, a nice fire in the grate completed the perfect sick room. Lord R looked far from death, sitting up smoking a cigarette. He told us he had come in the previous day suffering from a slight cold.”

Richard and the dean, hoping for the same kind of service as the Earl, were disappointed to be shown in to a cold cell with two mattresses on the floor and no fireplace….the floor littered with old tins and newspaper. “I didn’t realise the Franciscans were so attuned to the requirements of the British aristocracy” muttered the Dean, sourly.”

Hugo de Burgh, almost in Switzerland now, fell down a crevasse in the “Grenz” (The Maneater”) glacier where, when he came to his senses at the bottom of the crevasse, he found himself to be lying among the frozen corpses of various other unfortunates who had fallen there and perished in the ice…. thanks to the efforts of his companion Reggie he was saved from sharing their icy tomb and went on to reach the safety of Zermatt on the 29th of september. He noted “I have been afraid in my life, but never so afraid as I was during that journey down the “Grenz”

This was the same day that Gerald, Peter and Van had waded the River Taro with their canine fellow traveller, Tosca,

Elizabeth, for her part, had written that evening

“GIC 30 today (if he is alive)”

She would not have any news to dispel this fear for over a month.

Solo ……. 24th Oct 1943

My fathers character was of an independent and self sufficient bent. I suspect that he probably relished this separation from his companions. He was also a man of the countryside… his pleasure was to be with horse and dog, out and about, and I think that the wilder the landscape the more he took delight in it…. While he very rarely spoke of his wartime experiences I have frequently heard him rhapsodise about both the Libyan deserts and the Italian wildernesses through which he had walked.…. And what a landscape he was now in!

The fighting further south had by now developed into much slower rhythms, more akin, in places, so one reads, to the trench warfare of the first war. No one was getting anywhere fast. And so for the (now lone) traveller the finish line had hardly altered from a month ago. The thing that had changed as they had come further south, though, was the likelihood of encountering Germans..it was now high.

Dick Carver and the Dean had been finding this out for themselves.

The morning after a couple of close encounters on the roads with German forces “they were chased out of a barn before dawn by the owner who claimed that a German convoy was approaching. The farmer said that German patrols had recently raided the village across the river. … they fled up the side of a hill and eventually arrived at a small farmhouse belonging to an elderly shepherd and his wife. All this couple could offer them to eat were chestnuts and lard. She was about to wrap them in an official-looking piece of paper when Richard noticed the signature of Kesselring on the paper.

“What is this?” he asked.

“It’s a notice from the Germans,” said the shepherd’s wife, “we were ordered to pin it up in the village last week.”

The poster described a long list of forbidden activities and offences. The punishment for assisting British or American prisoners was death by firing squad and the burning of any farm that had harboured them. As they read it out, the shepherd’s wife laughed and finished rolling up their small gift. Richard was stunned by the unflinching bravery of these people. When they had eventually eaten the lard and the chestnuts, Richard and the Dean used the poster as toilet paper.”

Through the lines ……… 30th October 1943

This last part of the journey was perhaps the most perilous, with the greatest chance of being captured or shot, owing to the heavy concentrations of German troops.

Fortunately, in such a mountainous landscape, it is almost impossible for a defensive line to cover every inch that it is designed to defend. There were, it would seem, plenty of gaps available; the problem was to find them!

And again fortunately, local people were almost invariably keen to share their knowledge of these gaps.. indeed many were actively seeking to get through the lines themselves.

Eric Newby was now working on a mountain farm, living an almost normal existence with the family that had taken him in. In the middle of October this idyll was shattered by the arrival of a German search party when he was, fortunately, at a village ball with the daughters. He was able to make good his escape to an even more remote mountain top farm where he was to remain until his eventual recapture by the Italian Fascist Militia at the end of the year.

Hugo de Burgh, now recovering in a hospice in the town of Visp in Switzerland writes “We interested ourselves in the soldiers of our own armies and dominions who drifted over the mountain passes from Italy and were collected at Visp to be fed rested and to some extent clothed. It was October , all had been very lightly clad and were now for the most part in rags. Many of the men came over with almost bare feet, bleeding and frost bitten. Some had not come at all; the gaping crevasses had claimed them; surprisingly few in view of the complete lack of food, clothing and mountain equipment.”

Stuart Hood and Ted were still at large on the other side of the country in the first week of November, and slowly heading south into the Garfagnana. “Standing on the edge of the valley we looked across to the marble

mountains of Carrara. These peaks gleamed like snow. The Allies were somewhere above Naples – 300 miles to the south”

Richard Carver and the Dean had fallen in with some allied parachutists who had landed behind German lines and were engaged in trying to extract escapers by sea to Termoli . The Dean successfully made that sea passage in the night of the 6th to 7th November. But Richard’s escape still had some time to run.

Elizabeth’s diary has a slightly more upbeat tone on the 2nd of November, writing-

“wire from liz quoting George Kitson – heard G and Peter reported walking right way on Oct 20th…. Feel quite light headed!”

Conclusion.

Some ten days after his arrival at Lucito, my mother finally heard that G had made it through and was to be sent home.

A series of her diary entries tell the tale;

Nov 16 …..got G’s letter in post office. Rushed to tell ST and fainted at her feet… sent off countless telegrams…… feeling quite moonstruck

Nov 18 …..another letter from G….. I unpacked and sorted G’s clothes and had a blissful time….

December 11….. Heard from Gerald at Liverpool and talked to him on telephone…. Quite unhinged me…. Never been so thrilled in my life

Dec 12…… Gerald home

December 13 ….got up 8 am, very cold and brilliant all day. C good and it was a continuation of the fairy tale.

Peter Burnes was recaptured but survived the war, and was a familiar visitor to the farm in the 50’s and 60’s.

Van Burton, as far as I know, was also recaptured but I believe survived to tell the tale too.

Eric Newby was recaptured by the Italian Fascist militia just before the New Year, having been betrayed by a pro Fascist villager. He was to spend the remainder of the war as a prisoner in Germany. When the war was over he worked in Italy for the commission that was attempting to recompense and thank the Italians who had helped the escapers. He was also reunited with the girl he had fallen in love with in Fontanellato Hospital, and married her. (His time in the mountains is the basis of his novel Love and War in the Apennines)

Stuart Hood was to remain at liberty and, having fallen in with a band of resistance fighters, adopted the dangerous and exciting life of a partisan until eventually being repatriated toward the end of 1944. (He recorded his experiences in his book “Pebbles from my Skull”)

Richard Carver, after the Dean’s departure, had eventually elected to carry on walking, but had, after a few days, found himself having to hide in a cave for a fortnight before being helped, with assistance from the Italian family who had been maintaining him during this period, to cross the front line and be reunited with his stepfather, General Montgomery, who was the British General on this front. Monty’s greeting to his stepson upon this reunion… “Where the Hell Have You Been?” forms the title of his son Tom Carver’s account of his father’s escape.

Hugo de Burgh signs off his brief account thus; “Before leaving Visp I called to thank the Swiss officers for heir kindness to us all. One of them said – Why not? If it had not been for the Battle of Britain in 1940 there would be no Switzerland.” His account of his journey from Fontanellato to Visp can be found in the third appendix of Ian English’s account titled “Home by Christmas?”

My father spent the rest of the war in a training role at Sandhurst, and when it was all over resumed his civilian life where he had left off.

However he had been marked in two major ways by his time in Italy.

The first was to be visible fairly quickly. While at Fontanellato another inmate, who in peacetime had been an agricultural lecturer, had provided, for the entertainment and instruction of anyone who might be interested, a course of classes in agriculture; my father, who was already interested by the subject, followed this course with a keen interest, and by the time they were released he was determined to leave his job with the timber firm that he had been with before the war and go into farming. A couple of years later he bought the farm at Pinkhill. Where he was to remain for the next 40 years.

The second was that he was deeply affected by the help he had been given by so many people from this deeply Catholic country, from impoverished peasants and country priests to wealthy landlords and monks. Over the next years, and I feel his Italian experiences certainly played into this decision even if they weren’t entirely responsible for it, he ended up, to the horror of many conventionally Anglican family members, converting to Catholicism.

Eric Newby, Dick Carver, Stuart Hood all returned to the Italian mountains in later times, for they had all, in different ways, made strong connections with Italian families with whom they had stayed. My father, having never spent more than a night – or possibly two – in the same company, never did so – perhaps also because the farming life that he had chosen did not provide large enough periods of time to indulge in foreign holidays – and as he was not generally of a storytelling disposition, we did not hear much mention of his experiences there.

However a few of the threads of that period ran on into his later life…. Pete Burne was a familiar face to my elder siblings, and I believe even made an extended stay at the farm when recovering from some health problems, while in later times he had a correspondence and some meetings with Eric Newby, as well as following the offerings of the Monte San Martino trust, (a trust set up to honour the bravery of the Italian population who had offered so much help and hospitality to escaping prisoners) His interest in and affection for the area and the people is also illustrated by the presence in his papers of a variety of newspaper cuttings and articles and literature.

He went to some effort to set down this record of his own journey from memory after the event.. ( I believe he wrote the account within the following year.)

That it remains so detailed and (mainly!) accurate is a testament, I believe, to the intensity of the experience and to the deep satisfactions he must have derived from rising to the many challenges which he faced. Although I doubt that he would have said this, his view being that he was merely doing what he had to do, I think that, in his heart, this experience was one of the high points of his life.

He would, however, have been the first to note that the most prominent feature of the whole experience was the courage and kindness of the Italian country people who, at such enormous risk to themselves, opened their hearts and their doors so invariably to him, as to so many other ex Pows at this time.